When calculating the payback of LED lamps compared to other alternatives (typically incandescent or fluorescent), one of the most important parameters is the lamp’s lifespan. LED lamps are generally more expensive than the remaining alternatives, so a significant part of the justification for their profitability relies on their longer lifespan, which translates into lower replacement costs and lower maintenance expenses.

The difference with the other parameters involved in the payback calculation (price, electricity consumption, and amount of light provided) is that the lifespan is not directly measurable right after purchasing the lamp. We have no way to verify that the provided data matches reality, so we are forced to trust the manufacturer’s “good faith.”

This post, like the rest of the blog, is written as objectively as possible, recognizing the virtues and defects of each technology. After all, I don’t benefit whether you buy LED or compact fluorescent lamps. As I often tell you, never fully believe the data provided by someone trying to sell you a product, an energy audit, or, in general, anyone with economic interests at stake.

It must also be said that not all manufacturers are the same. Generally, the salespeople of prestigious brands tend to have a high degree of sincerity when expressing the characteristics of their products, even when it harms their product. However, other brands do not have the same interest in protecting their brand and promise the moon and the stars just to sell more.

Doesn’t it seem strange to you that quality manufacturers (Philips, Osram, etc.) indicate a shorter lifespan on their lamps compared to alternatives that cost 2 to 3 times less, or bought from the Chinese market? Always be wary of bargains.

Truths

LEDs are enclosed in a plastic package that is exceptionally durable. They are also highly resistant to external agents. A correctly manufactured LED under optimal operating conditions can achieve a lifespan of up to 100 thousand hours.

Furthermore, unlike conventional lamps that have a lifespan after which they stop working (they burn out), LEDs do not have, a priori theoretically, reasons for a failure that would cause them to completely shut off.

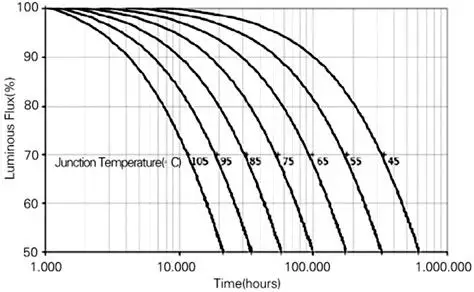

On the contrary, LEDs undergo a progressive degradation process. That is, as time passes, they progressively provide a smaller amount of light. The lifespan typically provided for an LED is the time for which the amount of light provided by the lamp decreases to 70% of its nominal value. The relationship between time and degradation is not linear, with the degradation rate increasing as time passes.

So, for now in this section, a positive point for the LED.

What They Don’t Tell You

Influence of Temperature

The operating temperature is one of the most important factors in its lifespan. Both the ambient temperature and the junction temperature (internal to the LED) reduce the LED’s life, with the latter being especially critical. An increase in junction temperature of 25ºC causes an LED’s lifespan to drop from 50,000 to 16,000 hours.

70 to 80% of the energy generated by an LED is converted into heat, which must be dissipated by the luminaire. This is the reason why LED luminaires have large heat sinks on the back. A correct design of the heat dissipation system is fundamental for a good lamp lifespan.

Influence of Current

Increasing the electrical current through the LED also means a reduction in its lifespan. Furthermore, although the amount of emitted light increases, its luminous efficiency decreases, i.e., the amount of light it emits in relation to its electrical consumption. A correct design of the lamp’s electronics is necessary, which keeps the electrical current constant and at the optimal value required by the LED.

Operating Conditions

The values provided for the lifespan and efficiency of LEDs are determined under so-called laboratory conditions, i.e., constant temperature of 25ºC, in a clean environment, in the complete absence of vibrations, environmental factors, solar radiation. Conditions very different from those the lamp will later be subjected to in its real operating regime.

Manufacturing Defects

Producing LEDs requires high-purity semiconductor materials, similar to those used in the electronics industry. However, it is impossible to have perfectly pure materials; there is always a small percentage of impurities, which affect the LED’s lifespan.

Beyond a certain degree of purity, reducing the percentage of inclusions requires complex and expensive manufacturing facilities and processes. Therefore, it is logical to expect that a cheap LED will have a much lower degree of purity in its components compared to those from recognized, higher-quality manufacturers.

Defects in Other Components

A very important factor that often goes unnoticed is the need for all components of the lamp, especially the electronics accompanying the LED, to also be of high quality.

Most of the LEDs we see “burned out” are not actually due to a failure of the LED itself, but to a failure of the electronics. In many cases, it is a simple failure in one of the solder joints, which due to vibrations or expansions end up breaking. These failures cannot be repaired on-site and force the lamp to be sent to the factory where they can probably be repaired.

Lamps with Multiple Emitters

LED lamps are actually made up of several individual LEDs. Let’s see the effect this grouping has on a lamp’s life. I will keep the math level as low as possible and avoid using terms like standard deviation or Weibull distribution. So if any of you (like me) enjoy statistics, don’t send me horse heads hold it against me.

Let’s take all the previous factors and synthesize them into a simulation of the probability of failure of an LED over time. We will simulate two experiments, each consisting of 100 individual LEDs. Each LED will have an average life of 35,000 hours, which is an appropriate value, although the results are extrapolable to any other average life.

We plot the results on what we will call a survival graph. Logically, LEDs do not fail simultaneously once the average life has passed. In reality, they fail randomly, at time values more or less concentrated around the average life. The graph shows on the Y-axis the percentage of LEDs that have failed after the number of hours shown on the X-axis.

The first thing we observe is that the red graph is “tougher” than the black one. The LEDs in the red experiment mostly last until 35,000 hours, and failure occurs near that time. However, the LEDs in the black experiment have a less concentrated distribution, with the first failures appearing earlier. In return, there are a number that exceed the average life, so the average life of both experiments is the same.

Now let’s run a simulation of 5 series of experiments, for lamps consisting of 1, 3, 5, 10, and 20 LEDs. We have adopted the curve from the red experiment because, being “tougher,” it is more beneficial for LEDs. In each series, 100 lamps will be simulated. The following graph shows the time until the first failure occurs.

It is observed that the lamp’s lifespan decreases as the number of LEDs that make it up increases. This is because, as mentioned, not all emitters fail simultaneously, but rather present a probability of failure around the average life.

The effect of this reduction is much greater the higher the dispersion of LED failures, i.e., the “softer” the survival graph of the individual LEDs. This is because, as we have seen, in a less concentrated graph, failures are more likely to occur at times well below the average life.

Well, so many graphs and so much math to justify a simple and evident reality. In a grouping of several light emitters, the time until the first one fails is substantially lower than the average life.

Now the question is: How many LEDs have to burn out in a lamp before considering it necessary to replace it? One, two…? 10% of those that make up the lamp? The answer depends on each user, but personally, for me, no burned-out LED is acceptable.

Conclusion

A manufacturer saying their LED lasts a lifespan of 30,000 hours only provides part of the information. They are not giving information about the dispersion of the distribution, nor about the influence of other components and factors. Furthermore, it is a value obtained under laboratory conditions, with controlled temperature, in the absence of vibrations, etc.

Now take this LED, put it in a lamp on the street, with vehicles passing by, rain, solar radiation, expansions and contractions caused by temperature changes (for example between day and night), add the probability of failure of other components (electronics and solder joints) and the fact that lamps are made up of several emitters, and see what that average life is reduced to.

Something simple to understand, which apparently those who replaced all the traffic light lamps didn’t know, arguing improvements in energy efficiency and savings in maintenance costs, and less than two years later half of the traffic lights have one or several LEDs off.

Another example I can tell you firsthand happened in a certain municipality where several high-pressure sodium luminaires (very high efficiency) were replaced with very low-priced LED luminaires, between 2 and 3 times cheaper than the competition. The manufacturer claimed to mount a high-quality LED made in the USA, but a simple internet search showed indications that this manufacturer was marketing a Chinese product from which they scraped off the name and put a label with their logo on top. Despite advising the client against it, the brand’s salesperson must have been excellent at his job because he convinced the municipality to install their luminaires. In less than a year, the luminaires were burned out and the city council had complaints that the lighting levels were much lower than before, which meant a lack of visual comfort. Needless to say, they did not remotely comply with regulations. This is what happens when things are done wrong and you ignore the prescription of those who advise you correctly.

The solution to these cases is, in reality, quite simple. Demand a warranty from the manufacturer. If they are so sure of their product as to use those values in a payback study, have them offer you a warranty that covers at least 80% of the lifespan. After all, they know the quality of their product and manufacturing process better than anyone. Why should you risk your money on an uncertainty that is actually the manufacturer’s responsibility, and which they know much better than you?

My advice is that when doing an LED payback study, you compute its lifespan as the warranty offered by the manufacturer, and in this way, you will avoid unpleasant surprises. And, as always, be wary of bargains.